Connecticut : Leah Ulbrich

Hartford, Connecticut is a city rich in history and cultural significance. Beyond being the capital of Connecticut, the city stands as a living testament to American history with neighborhoods adorned by centuries-old architecture and landmarks. The Mark Twain house, the oldest public art museum, the oldest publicly funded park and the oldest continuously published newspaper.

It is home to many festivals celebrating an inclusive environment and keeping the arts in the forefront of the community. Hartford is known as the insurance capital of the world as many companies call Hartford home.

Before the Salem witch trials, eleven women and men were executed by hanging. Alice Young was the first witchcraft execution in American history on May 26, 1647 in Hartford.

This may be one of the first trials on the history records, you know that we don’t discuss closed cases and that is why we are navigating advocacy in Hartford, Connecticut.

Leah Wynnette Baskins was born January 15, 1971. She grew up in eastern Connecticut and later her family moved to Fairfield County and then again to the New Haven area.

She loved to care for other people and at one point mentioned taking a career in the nursing field. She had an artistic flair as a child and she enjoyed writing poetry.

As a teenager, Leah struggled on and off with drug abuse and with the help of her father, entered a counseling program. She graduated from the program and then at 19 she met Robert Ulbrich.

Robert was the son of Fred and Joanne Ulbrich. Fred was the president of Ulbrich Stainless Steel and Special Metals of Wallingford and North Haven. The two fell in love and got married when Leah was 19 in 1989. They had two children, one boy and one girl. Leah loved being a mother and was madly in love with Robert but the marriage only lasted 2 years and the two divorced in 1991.

Joanne stated in an interview with a reporter for the Record-Journal that the divorce took its toll on Leah. She relapsed and her addiction took hold. Leah’s mother shared custody of her kids with Robert after the divorce. The Hartford Courant reported this was a decision because police found her home in subpar living conditions for children and drug paraphernalia was found in June of 1993. This caused Leah’s addiction to spiral.

In the following two years, Leah had a few run-ins with law enforcement, mostly as a result of her addiction. One leading to her serving 9 months in jail in 1994.

By the summer of 1995, Leah was making significant efforts to stay sober. She voluntarily checked into the Stonehaven Program Middletown, Connecticut rehabilitation program. She successfully graduated and developed an after program plan. Leah regularly attended Narcotics Anonymous meetings, was residing in a halfway house for recovering female addicts in Springfield and was thriving. Having dropped out of high school as a teenager, she was also actively working towards gaining her GED.

Around October 19, 1995, Leah moved out of her halfway house and cut ties with her family. They were concerned that Leah had relapsed.

Before I get into further details, I have to tell you the struggles I had finding some of this information. I called law enforcement multiple times to get files on Leah’s story. Thankfully I have been drinking Magic Mind to keep me motivated and on task. Usually I am all over the place when it comes to getting work done.. Being what I call waffle brained, I hop from task to task until they are completed. When I take the little shot of Magic Mind the nootropics keep my concentration where it needs to be.

On October 29, 1995, at 4:45 am, Bill Flemming was out making his morning route delivering the Hartford Courant when he passed a dark 90s model Nissan Maxima or Altima parked near the intersection of Locust Street and East Elliot Street. Inside he noticed a male in the driver seat hit a woman in the passenger seat. The woman, who later would be identified as Leah, started screaming for help.

Bill turned around in an attempt to help her but the driver forced Leah out of the passenger seat and peeled off down the street. Leah’s arm was stuck in the seatbelt and she was being drug at a high rate of speed down the road.

Bill sent a distress call to his dispatcher who then phoned 911. According to reports, the 911 call came in at 4:50am. The chase escalated to over 60 miles per hour and Bill could no longer keep up in his delivery vehicle. Officer Martin Burke encountered the vehicle as it was driving along Wethersfield Avenue. He turned around and began chasing it as well. Unfortunately the driver was able to speed out of view but Officer Burke followed the road to where he found Leah.

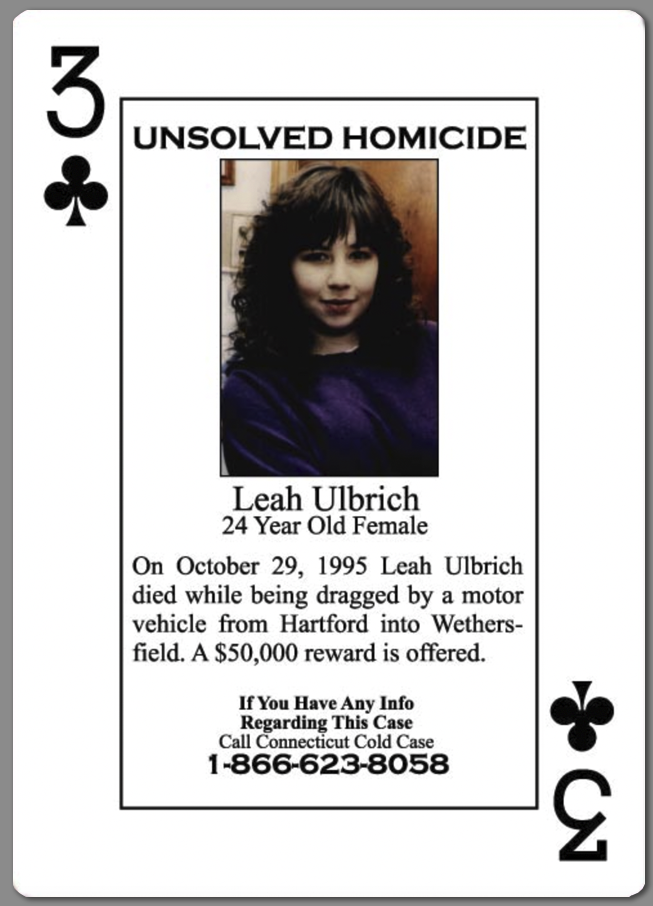

Leah was dragged for over four miles on the paved road before her arm came loose from the seatbelt. This created the largest crime scene in Connecticut history. Leah’s body had trauma on over 80% of her body. She was deceased when Officer Burke found her lying on the side of the road off of Jordan Lane in Wethersfield.

This area of Hartford is an industrial park but it was also a known area where solicitation regularly occurred. Many people witnessed this horrific event. Along the four mile crime scene, residents reported hearing Leah’s screams. Various other witnesses attempted to provide more information about what they had seen. One reported the car was a dark color, maybe black, burgundy, blue or brown.

Initial investigations led law enforcement to believe that perhaps Leah was meeting a dealer for drugs and that the male in the driver's seat attempted to push Leah out of the vehicle and her arm was tangled causing her to be dragged.

As more witnesses came forward and the case began to form, one witness said they believed the car had a temporary paper tag. They also learned that a second 911 call came into dispatch as it was occurring. A woman utilized a call box on the corner of Wethersfield Avenue and Elliot Street. She only said that she had seen a woman being dragged by a car and then ended the call. Law enforcement was never able to identify this caller or speak further with her. They even put out a request to the public hoping to speak with her.

The temporary tag tip seemed to be the most promising lead at the time and detectives pulled records of every paper tag connected to a Nissan Maxima or Nissan Altima in the state of Connecticut. They tracked down every single one and were not able to find the vehicle that was used for the homicide.

Leaning further into the seatbelt theory, detectives reached out to mechanics and auto-body shops asking if anyone had sought out seat belt repair, but again found themselves at a dead end.

As autopsy reports returned days after her death, the cause of death was ruled as extensive blunt trauma.

Connecticut’s governor, John G. Rowland offered a $20,000 reward for information leading to an arrest and conviction just a few weeks after Leah’s death hoping to stir up credible leads. Today that would be just under $40,000. Again no new leads surfaced. Detectives were still also attempting to make a connection between Leah and the driver. They had no evidence to support if there was a connection between the two.

According to the Hartford Courant, witnesses believed that the driver was a man in his late 20s. Perhaps white or hispanic and that he had slicked - back dark hair. Given that the murder happened before the sun had risen, it was difficult to recall exact details. Based on interviews and testimonies, Robert was ruled out as a suspect as well as other ex-boyfriends and associates of Leah’s.

It wouldn’t be until March 1996 that investigators would receive some information that would help their investigation. Metallic blue chips were found on Leah’s clothing narrowing down the color of the car.

May 16, 1996, a report by the Hartford Courant stated that police had a suspect in Leah’s death. Chief John Karangekis said “they were looking strongly at a suspect and significant evidence” but the very next day, the Courant reported that police stated they had no lead suspect. Tests reported that fibers and paint from the suspects car did not match. Chief Karangekis recanted and stated that he may have shared inaccurate information.

While this suspect was never named publicly, according to Medium.com, it was a 24 year old who had been arrested on multiple kidnapping and sexual assault charges after Leah was murdered. His MO was to pick up several women and drive them to secluded areas, assault them then force them out of the car.

In 2000 and 2001, 7 officers in the Hartford Police Department were convicted of sexual misconduct. This brought attention back to Leah’s case as one of the officers had a possible involvement. Ultimately the seven received sentences ranging from probation to 10 years in prison.

In 2002, law enforcement revealed that an electronic cord was found with Leah’s remains. Whether or not this was something that came from the car Leah was being dragged by or was already on the side of the road is unknown. They also did not share what type of electronic device this cord would have belonged to.

Leah’s name would not appear in a newspaper again for 18 years.

On the 24th anniversary of Leah’s death, the Hartford Courant ran an article renewing interest in Leah’s story. They reported that evidence was tested again in years past hoping for help from technological advancements. Unfortunately the tests were unsuccessful.

Leah’s children, adults now began advocating for their mother. Her son began interning with a non profit group in Connecticut called the Survivors of Homicide. It provides families of homicide victims with support services. In the article, her son stated that he realized that good could come from a bad situation. It brings people together and allows them to find support in one another.

His sister credits her strength from the circumstances of her childhood.

Leah’s ex-husband Bob passed away in 2001 and their children are still hoping for answers. They have started sharing her story more as a way to keep their memory alive.

Law enforcement is still seeking answers. If you or someone you know remembers a 90s model Nissan Maxima or Altima blue car or similar body style please contact the Hartford Cold Case Unit at 860.548.0606. The reward has since been increased to $50,000.